The digital divide - the economic gap between those with internet access and those without - is a growing problem throughout the world, and not just in developing economies. Many people are trying the bridge this gap, and here are some of their stories.

As a teenager, Marlin Jenkins was homeless for a couple of years.

Now, aged 45, he is trying to help the 40% of households in New York's Bronx district without internet get online.

"When education, banking and healthcare are online, and huge groups can't leverage these tools, the people who struggle most are struggling harder," he says.

Mr Jenkins and his two brothers, one of whom has cerebral palsy, were raised by a single mother. When the family's housing in Yonkers, New York fell through, his mother moved them 50 miles upstate in search of somewhere to live - a search which proved unsuccessful and resulted in a period of homelessness.

He still managed to gain his high school diploma though, and after university worked for telecoms giants Verizon and AT&T, then founded a gaming start-up.

He says his first response to having been homeless was that "I needed to make as much money as possible out of college" to provide for his family, but says the 9/11 terror attacks later changed his perspective, deciding instead to "cut my profit to give more back".

Eight years ago, he passed a five-year-old girl outside a Bronx library on his way home.

"She was crying to her mother about not being able to finish her homework because she didn't have internet access at home, and the library was closed," he says.

"I'll never forget the mother's face, she was distraught and it was heartbreaking."

The experience inspired him to found Neture in 2015, a start-up offering low-income Bronx residents free access to online education, healthcare and finance resources. Residents can also buy 25 megabit per second (Mbps) broadband for wider web surfing if they want to.

Neture is making its first large-scale deployment this month in a 12-storey apartment block.

"People say, why don't you create a food platform, or something else tech-driven. But if you can't connect to the internet, it doesn't matter what else you can do," says Mr Jenkins.

Today, just over half - 51.2% - of the world's population is online, says the Geneva-based International Telecommunication Union.

This means billions of people are missing out on the clear economic benefits internet access can bring.

Some studies have suggested that every 10% increase in broadband penetration increases a country's economic output by 1%, and other country-specific studies in Africa have established a clear link between poverty alleviation and access to mobile internet.

"High-speed internet has a positive impact on poverty reduction," says Olivier Vanden Eynde, founder of Close the Gap, an organisation working to bridge the digital divide in a sustainable way. "There are very interesting and well-respected studies.

"Better access to information increases farmers' effectiveness in agriculture," he says. "And fintech [financial technology] can make transactions more effective and less corrupt."

In developed countries, 85.3% of households have web access at home. In the 47 poorest countries, the figure is 17.8%.

But the digital divide affects underprivileged people in rich countries too.

In Mississippi, for example, one of the most impoverished US states, 38.1% of households aren't online, says the US Census Bureau.

Compare this to New Hampshire, one of the wealthiest states, where the figure is 15.1%.

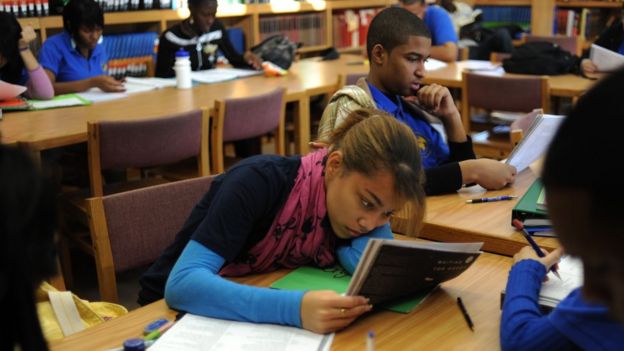

In the US as a whole, five million households with school-age children don't have internet access.

Lack of competition in US regional markets drives the average monthly cost of broadband in the US to $66.17 (£51.55), says the price comparison website cable.co.uk. This is 50% higher than the monthly average in Germany, for example.

And with faster - probably more expensive - 5G mobile internet coming in the next year or so, this could add "another new digital divide, with people building new technologies and applications that people who can't afford 5G can't access", says Xiaoqun Zhang, a professor at the University of North Texas.

One region that does well is the former Soviet Union, where infrastructure is well developed and markets are healthily competitive.

Ukraine has the world's cheapest broadband, at an average monthly cost of $5. Russia ($9.77), Belarus ($10.46) and Moldova ($11.28) are all in the next five cheapest, too.

But in African countries such as Sierra Leone, Mali, Namibia and Ethiopia, the average monthly cost of broadband is more than $125.

.

In large African cities like Accra, Ghana, "broadband internet access is not an issue", says Enock Seth Nyamador, a 2018 computer science graduate and founder of the OpenStreetMap Ghana community.

But in Keta, the fishing community in Ghana's southeast where Mr Nyamodor grew up, a third of the 23,000 population lives under the poverty line of $1.90 a day.

"When you go to the remote areas, that's where you have issues - network operators don't reach most of the communities," he says.

And using smartphones to access the internet there is "pretty expensive - the cheapest I could buy would be 70 cents (3.4 Ghanaian cedi, or 54p) for 500 megabytes of data".

That's more than a third of what many people in Keta live on every day.

And so in Ghana, just 6% of men and 2.1% of women say they use the internet, according to the country's statistical service.

This comes despite 46.2% of Keta's men and 38.4% of its women saying they have a mobile telephone. Only 2.9% of Keta households own computers.

Another problem, says Mr Nyamador, is the Google Map car doesn't go to places like Keta.

"When you look on Google Maps, it is a product targeted towards cities, where money comes from. But what about villages where there is a need for development and map data?" he says.

Another problem is accessing the internet in a language you understand.

India has 22 official languages and hundreds of others spoken, but just 10% of its population can speak English.

Many smartphone buyers "don't know how to type, because they have never used a digital device for typing", says Rakesh Deshmukh, chief executive of Mumbai-based Indus OS.

So Mr Deshmukh has been developing keyboards and app stores for each of India's official languages, along with a "swipe to translate" feature that can translate English messages into a user's mother tongue.

The global digital divide is reinforcing inequalities of wealth between and within countries.

But people like Marlin Jenkins, Enock Nyamado and Rakesh Deshmukh are doing their best to build bridges across it.

Share the story

As a teenager, Marlin Jenkins was homeless for a couple of years.

Now, aged 45, he is trying to help the 40% of households in New York's Bronx district without internet get online.

"When education, banking and healthcare are online, and huge groups can't leverage these tools, the people who struggle most are struggling harder," he says.

Mr Jenkins and his two brothers, one of whom has cerebral palsy, were raised by a single mother. When the family's housing in Yonkers, New York fell through, his mother moved them 50 miles upstate in search of somewhere to live - a search which proved unsuccessful and resulted in a period of homelessness.

He still managed to gain his high school diploma though, and after university worked for telecoms giants Verizon and AT&T, then founded a gaming start-up.

He says his first response to having been homeless was that "I needed to make as much money as possible out of college" to provide for his family, but says the 9/11 terror attacks later changed his perspective, deciding instead to "cut my profit to give more back".

Eight years ago, he passed a five-year-old girl outside a Bronx library on his way home.

"She was crying to her mother about not being able to finish her homework because she didn't have internet access at home, and the library was closed," he says.

"I'll never forget the mother's face, she was distraught and it was heartbreaking."

The experience inspired him to found Neture in 2015, a start-up offering low-income Bronx residents free access to online education, healthcare and finance resources. Residents can also buy 25 megabit per second (Mbps) broadband for wider web surfing if they want to.

Neture is making its first large-scale deployment this month in a 12-storey apartment block.

"People say, why don't you create a food platform, or something else tech-driven. But if you can't connect to the internet, it doesn't matter what else you can do," says Mr Jenkins.

Today, just over half - 51.2% - of the world's population is online, says the Geneva-based International Telecommunication Union.

This means billions of people are missing out on the clear economic benefits internet access can bring.

Some studies have suggested that every 10% increase in broadband penetration increases a country's economic output by 1%, and other country-specific studies in Africa have established a clear link between poverty alleviation and access to mobile internet.

"High-speed internet has a positive impact on poverty reduction," says Olivier Vanden Eynde, founder of Close the Gap, an organisation working to bridge the digital divide in a sustainable way. "There are very interesting and well-respected studies.

"Better access to information increases farmers' effectiveness in agriculture," he says. "And fintech [financial technology] can make transactions more effective and less corrupt."

In developed countries, 85.3% of households have web access at home. In the 47 poorest countries, the figure is 17.8%.

But the digital divide affects underprivileged people in rich countries too.

In Mississippi, for example, one of the most impoverished US states, 38.1% of households aren't online, says the US Census Bureau.

Compare this to New Hampshire, one of the wealthiest states, where the figure is 15.1%.

In the US as a whole, five million households with school-age children don't have internet access.

Lack of competition in US regional markets drives the average monthly cost of broadband in the US to $66.17 (£51.55), says the price comparison website cable.co.uk. This is 50% higher than the monthly average in Germany, for example.

And with faster - probably more expensive - 5G mobile internet coming in the next year or so, this could add "another new digital divide, with people building new technologies and applications that people who can't afford 5G can't access", says Xiaoqun Zhang, a professor at the University of North Texas.

One region that does well is the former Soviet Union, where infrastructure is well developed and markets are healthily competitive.

Ukraine has the world's cheapest broadband, at an average monthly cost of $5. Russia ($9.77), Belarus ($10.46) and Moldova ($11.28) are all in the next five cheapest, too.

But in African countries such as Sierra Leone, Mali, Namibia and Ethiopia, the average monthly cost of broadband is more than $125.

.

In large African cities like Accra, Ghana, "broadband internet access is not an issue", says Enock Seth Nyamador, a 2018 computer science graduate and founder of the OpenStreetMap Ghana community.

But in Keta, the fishing community in Ghana's southeast where Mr Nyamodor grew up, a third of the 23,000 population lives under the poverty line of $1.90 a day.

"When you go to the remote areas, that's where you have issues - network operators don't reach most of the communities," he says.

And using smartphones to access the internet there is "pretty expensive - the cheapest I could buy would be 70 cents (3.4 Ghanaian cedi, or 54p) for 500 megabytes of data".

That's more than a third of what many people in Keta live on every day.

And so in Ghana, just 6% of men and 2.1% of women say they use the internet, according to the country's statistical service.

This comes despite 46.2% of Keta's men and 38.4% of its women saying they have a mobile telephone. Only 2.9% of Keta households own computers.

Another problem, says Mr Nyamador, is the Google Map car doesn't go to places like Keta.

"When you look on Google Maps, it is a product targeted towards cities, where money comes from. But what about villages where there is a need for development and map data?" he says.

Another problem is accessing the internet in a language you understand.

India has 22 official languages and hundreds of others spoken, but just 10% of its population can speak English.

Many smartphone buyers "don't know how to type, because they have never used a digital device for typing", says Rakesh Deshmukh, chief executive of Mumbai-based Indus OS.

So Mr Deshmukh has been developing keyboards and app stores for each of India's official languages, along with a "swipe to translate" feature that can translate English messages into a user's mother tongue.

The global digital divide is reinforcing inequalities of wealth between and within countries.

But people like Marlin Jenkins, Enock Nyamado and Rakesh Deshmukh are doing their best to build bridges across it.

Share the story

No comments:

Post a Comment